Go or no-go? The business case provides the answer

Every supply chain project begins with a close check of its economic efficiency. After all, investments in a new solution should not only pay off, but also lead to noticeable cost reductions over the medium and long term. And it is this savings potential that must be determined in advance – precisely, comprehensibly, and with a solid foundation – because without a specific business case, top management will not provide the necessary budget approval. But what exactly are the decisive factors to calculate the success of a SCM solution?

Internally and externally: The business case examines everything

First, it is important to clearly map all the affected processes. This step applies not just to internal processes such as demands planning, awarding of contracts, production, plant-to-plant supply for component manufacture, or final assembly. Rather, all the relevant partners for those processes that take place outside the company itself must be involved as well. These partners typically include transporters, carriers, customs service providers and warehouses in addition to the suppliers.

In short: At issue is an end-to-end examination of the entire supply chain process. On the basis of this analysis, savings potentials can be divided roughly into two categories.

1) Additional value in place of inefficient processes

The first category is process costs. In this case, everything revolves around the question: What costs arise today from unstructured and recursive communication that does not create value and whose expense can be eliminated through a systematically planned and implemented supply chain? An alarmingly high share of internal and external collaboration still takes place via Excel, phone, fax and e-mail. This is not only time-consuming, but in particular inefficient and error-prone.

If this work is eliminated, personnel requirements could be reduced accordingly in the future, for instance. However, experience has shown that this rarely happens. Instead, the freed-up human resources are oftentimes used for value-creating activities, which increases the efficiency of a company’s own organization without having to hire additional employees.

For the business-case analysis, this means that the theoretically necessary increase in headcount to secure and increase the organization’s performance is set off against the increased efficiency of the supply-chain solution.

2) Lower expenses

The second category of savings potentials lies in the reduction of explicit costs. For instance, costs for warehousing can be reduced and/or tied capital can be decreased if internal and external movements are transparent on the material master data-number level. Another example of savings relate to avoidable extra tours and expedited shipments. Also, lower purchase prices can be achieved through auctions and the company-wide bundling of all demands.

Reductions in these costs directly affect a company’s corporate results. For the business case, this means that running costs in precisely these areas can be set off against project costs or costs for the operation of the supply-chain solution.

Don’t forget the roll-out phase in the business case

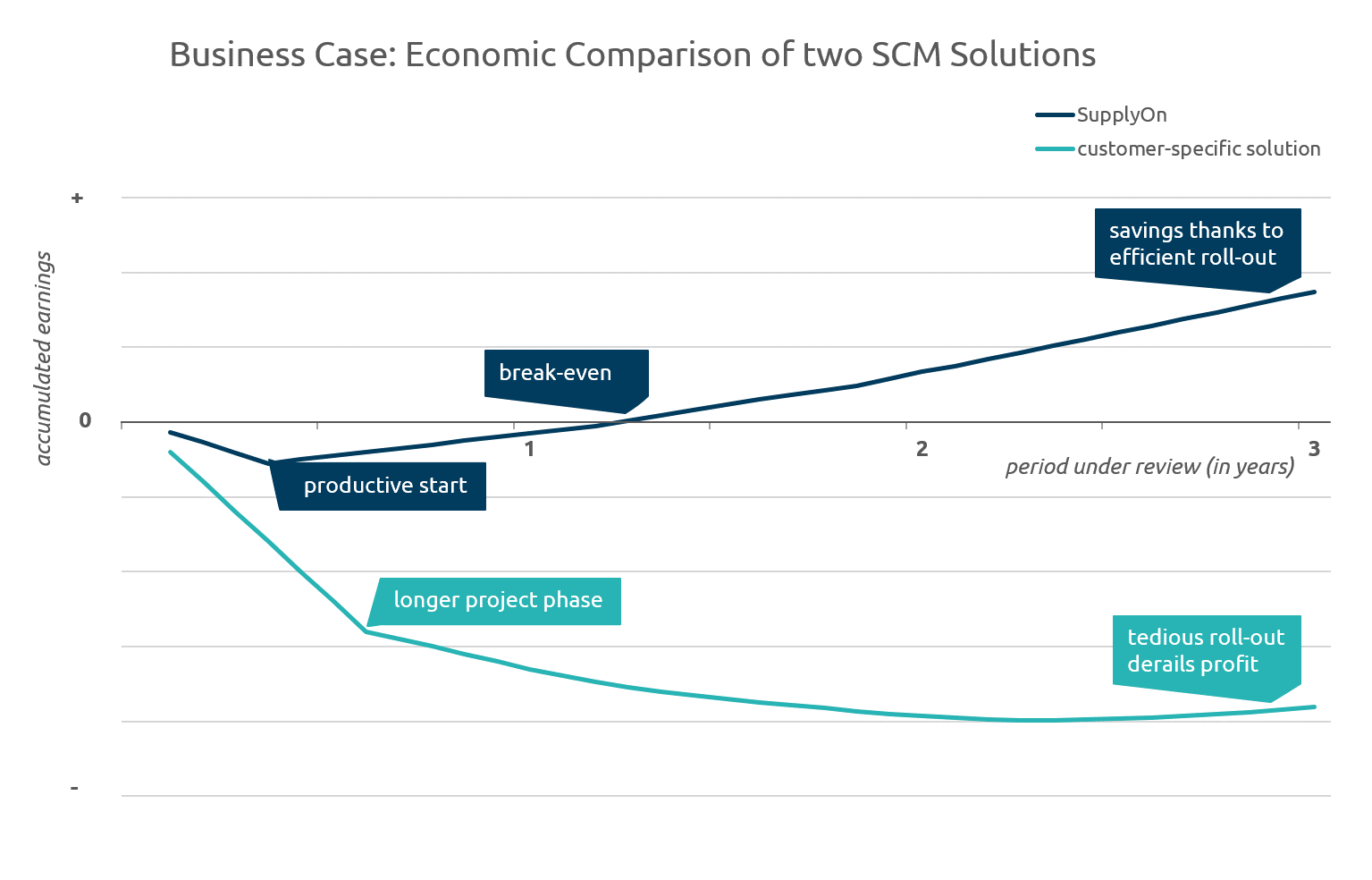

However, it is very important to realistically consider how quickly these cost-cutting targets can actually be achieved. After all, a supply-chain solution does not solely involve internal processes; it also focuses on collaboration with external partners pursuing their own objectives. It has been our experience again and again that an overly optimistic project roll-out is assumed here.

In other words: how many suppliers and external partners can be integrated how quickly is often either not considered or at least underestimated.

For suppliers, every additional or new proprietary supply-chain solution from one of their many customers is associated with considerable, long-term additional expenditure. The more and the longer suppliers and other partners hesitate to apply the new solution, the less accurate the original calculation will be in the end.

This is where a central collaboration platform like SupplyOn can play to its strengths, connecting more than 30,000 companies and thereby significantly accelerating the roll-out process. As a result, the project goals outlined by the business case can actually be achieved.

The moment of truth: business case or no case?

In the final step, the results of both cost-saving analyses must be considered over the course of time. Over a period of three to five years, it can be determined relatively quickly whether the identified costs will result in a positive balance when set off against the project and operational expenses for the planned supply chain solution. In other words: whether the project will pay off.