Supply chain vs. supply chain – does the paradigm of competing supply chains really apply?

“Supply Chain vs. Supply Chain – The Hype and the Reality”. One of my colleagues recently found an article with this title in the internet, and for a number of reasons it struck me as highly interesting and also relevant. For one thing, it was published in 2001, over 16 years ago, in the technical journal ‘Supply Chain Management Review’ (www.scmr.com).

This was before the concept of supply chain management had really become established, when the demarcation between SCM and logistics was at best woolly. At the time, the ‘Council of Supply Chain Management Professionals’ (CSCMP) was still called the ‘Council of Logistics Management’ (CLM) and value-creation networks were nowhere near as global as they are today. Russia, India, and Brazil were not yet among the world’s ten largest economies, and China’s gross domestic product was only around one ninth of its current size.

Who is competing in the age of the digital supply chain – individual companies or entire supply networks?

Even at the time, the increasing importance of SCM prompted the question of whether we should expect in future to see competition no longer being between individual companies, but between entire supply chains or supply networks.The article’s authors – James Rice (Director of MIT’s Integrated Supply Chain Management Program) and Richard Hoppe (McKinsey) – carried out a survey of more than 30 supply chain experts from industry, universities, and consulting.

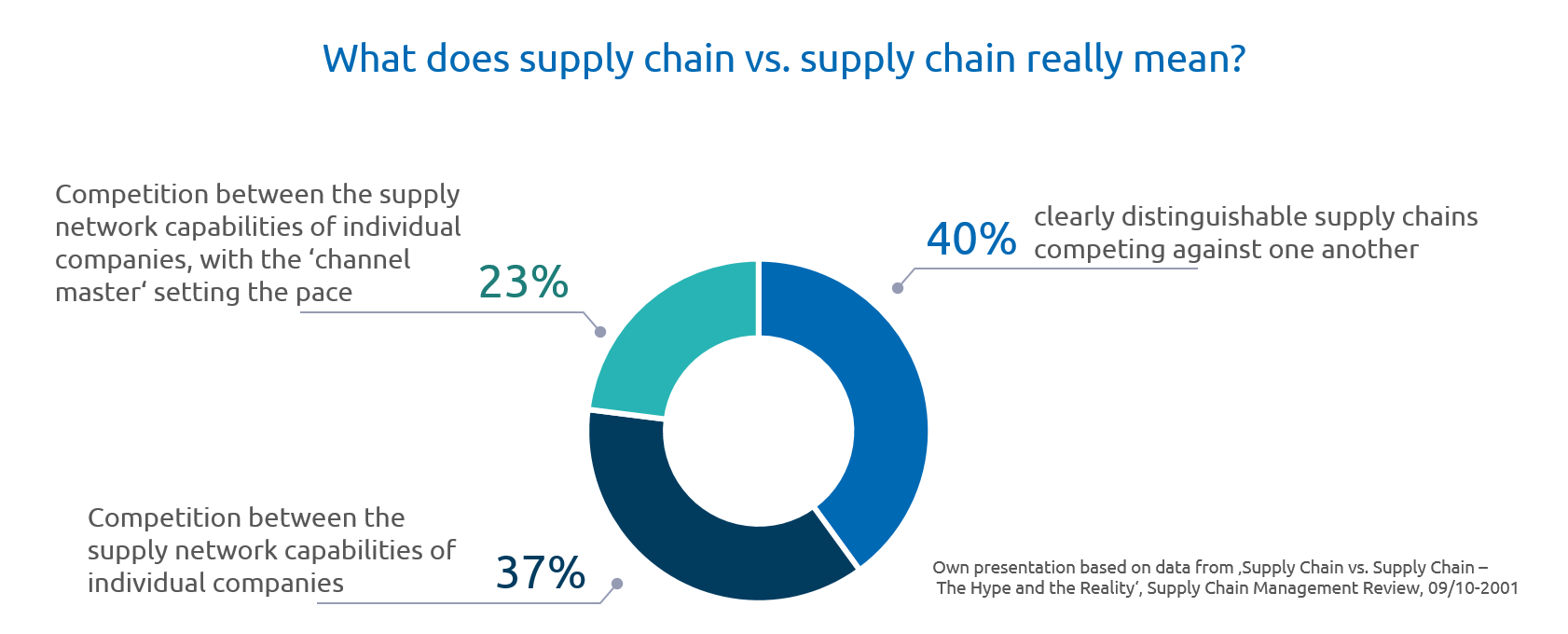

70 % of the respondents agreed that the expression “supply chain versus supply chain” aptly describes what we see in practice. The industrialists were most strongly convinced of this (75 %), followed by the consultants (72 %) and the university representatives (60 %). However, they disagreed about the exact meaning of the expression, and this makes it clear that the question is by no means trivial.

Subject to interpretation

The concept of ‘supply chain vs. supply chain’ was interpreted in the following three different ways:

Case 1: Different, clearly distinguishable supply chains competing against one another in the purest sense of the word (about 40 % of respondents).

Case 2: The capabilities of supply networks of individual companies are in competition with each other (about 37% of respondents), in particular:

a. The costs and/or service capabilities of their internal supply networks, such as can be measured in terms of the supply network’s ‘efficiency,’ ‘effectiveness,’ and ‘responsiveness’

b. The design of the internal supply network in relation to the underlying strategic structure and the procurement models, principles, and processes used (build-to-stock or build-to-order, etc.).

Case 3: Competition between the supply network capabilities of individual companies, with the most powerful company (the ‘channel master’) setting the pace (about 23% of respondents)

We can already see from these different interpretations that there is no clear answer to our original question. Therefore, the authors defined various cases to which the paradigm of competing supply chains – depending on the interpretation of the term – applies to a greater or lesser extent.

It seems to fit quite well for all those supply chains in which there are clearly delineated manufacturer groups with little or no overlap of the suppliers in the various tiers.

At the time the article was written (2001), this included for example the fashion industry.

Supply networks: performance and efficiency are what counts

The automotive industry, with its manifold suppliers who simultaneously belong to numerous different OEM networks, conversely belongs in category 2. The authors consider the performance and efficiency of the supply networks to be the key differentiation characteristic. To a very marked degree, this includes the ability of an enterprise to gain an advantage by optimally exploiting the performance and uniqueness of the customers (downstream) and suppliers (upstream) with which it is networked, as a way of enhancing its competitive differentiation.

Worthwhile areas in this context include joint product development programs, participation in innovative supply concepts (JIT, VMI, etc.), and even joint marketing activities.

Of particular importance: A well-functioning and efficient collaboration between partners, which have direct touch points within digital supply networks. Theoretically, it might be useful to develop comprehensive concepts for supply chain optimization. However, the authors consider it more practical, realistic, and effective for each individual company to optimize its own network capabilities in the directly adjacent partner network toward both customers and suppliers, as appropriate for its role and position.

According to the authors of the study, it is particularly important to place the emphasis here on integrating external partners rather than acquiring additional knowledge and skills, because the latter can be copied faster and more easily than a functioning and stable integration.

Possible examples for such an integration:

- Involve suppliers in product development as closely and as soon as possible

- Involve customers and suppliers in critical decision-making processes

- Closely link and integrate cross-company processes between neighboring partners in the supply chain

In the third case , the most powerful and influential business determines the processes and constraints of the entire digital supply network. This company is referred to as the ‘channel master.’ One example given is from the 1990s, when the Chrysler Corporation imposed very specific requirements on its suppliers at various levels and aggressively incorporated these requirements into its own processes. The suppliers themselves had very little chance of implementing their own ideas, at least in regard to supplying goods to Chrysler.

Current status

Today’s automotive industry must be considered a mixture of cases 2 and 3: Some companies – particularly OEMs – impose extremely specific requirements on their suppliers when it comes to supply chain related processes. Suppliers must comply with and implement these demands or risk losing a lot of business. In both cases, however, narrow procedural links to a company’s immediate neighbors in the supply chain do appear to generate definite benefits for those in the respective supply network. For direct competitors, it is more difficult and takes more time to match these benefits than it does for individual capabilities that are acquired separately.

In summary, we can state: The paradigm of mutually competing supply chains really does not apply to it’s major sub-sectors of the manufacturing industry – such as automotive, mechanical, plant engineering, and aerospace – unless competition is restricted to supply network capabilities (case 2, see above).

What can a manufacturing company do to improve the efficiency of its supply chain and its own competitiveness?

Following the approaches suggested in the study, each individual company should exploit its own position and role in order to really optimize its interaction with its neighboring supply network partners (i.e., customers and suppliers). This idea leads us to the hypothesis that more efficient, more transparent, and faster parts of the network can generate certain advantages when competing with less good parts. Consequently, companies that belong to above-average networks could generally achieve more overall.

What exactly can be concluded from this? Individual companies – often belonging to several industries and different networks – should exploit their position and role as far as possible in order to optimize their cross-company supply chain processes, both toward their neighboring customers and with their own suppliers.

It is also advisable to show those partners the advantages of improved digital supply chain processes, so that they can also initiate and implement corresponding improvements themselves. Successfully carried out, this will enable initially the most competitive companies, subsequently the most powerful parts of the network, and eventually all the regional industries to hold out more effectively against the competition.

Some examples of this type already exist, and the particularly promising projects are those initiated by OEMs.

Example AirSupply

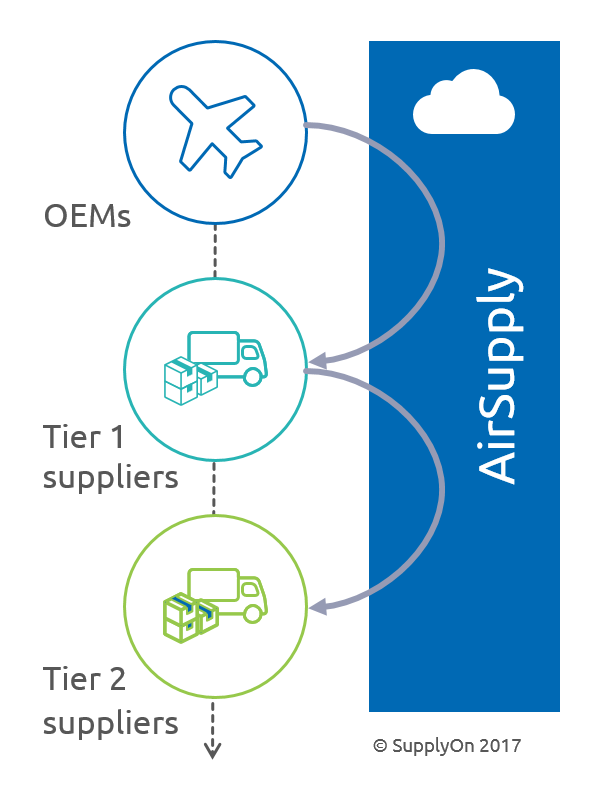

For example, several years ago Airbus recognized that the European aerospace industry could positively differentiate itself from the North American aviation sector if it replaced its host of individual supply chain solutions with a uniform collaborative solution. The best part:The solution could then not only be made available to the major OEMs but could also be used at each individual link of the inbound supply chain.The only prerequisite being that the procurement processes are suitable and highly collaborative).

In 2009 they decided to develop such a standardized solution: AirSupply. This has now been in operation for over six years, and is already being used successfully by over 2,000 aerospace companies. Meanwhile, the platform is being used for up to four levels of the supply network This offers the basis for standardized and seamless best practice processes to provide uniform processing throughout an entire industry.

The original article ‘Supply Chain vs. Supply Chain’ by SCMR can be found here.

Credits: This blog post was originally published by Werner Busenius on January 25,2015. In October 2017, it has been revised and updated.